Fault Lines Shows the Nation's Most Socioeconomically Segregating School District Borders

While attending America Succeeds’ always excellent EdVenture conference in Boise in September, we had the opportunity to acquaint ourselves with a non-profit organization that produces arguably the most compelling and visually appealing education data we’ve seen.

We can all learn from its work.

EdBuild, based in Jersey City, N.J., won national acclaim recently for Fault Lines, its report on the most socioeconomically segregating school district borders in the U.S. The report and its highly localized data garnered a great deal of national and local media coverage.

In addition to conducting sophisticated research and data analysis, EdBuild provides interactive maps on its website that allow readers to zoom in their searches and customize and localize the massive data set.

At Colorado Succeeds, we believe strongly in the power of data to inform decisions that drive improvements to public schools. Our Colorado School Grades website provides a visually appealing, easily digestible format for parents to investigate the quality of public schools.

That’s why we admire what EdBuild has done with Fault Lines. So we decided to delve more deeply into the organization, its work, and its Colorado-specific findings.

“Our feeling is that an interactive visualization gets people engaged with the issue,” Zahava Stadler, EdBuild’s manager of policy and research told us during a recent phone call. “The more dynamic the presentation the more likely people are to pay attention and absorb it.”

EdBuild’s mission is to “bring common sense and fairness to the way states fund public schools.” This includes advocating for a system that “funds an equal chance in life for every child, regardless of their zip code.”

Huge disparities in poverty between neighboring school districts flies in the face of this mission, especially when district boundaries appear arbitrarily drawn, or, in some cases, drawn to foster economic segregation, Stadler told us.

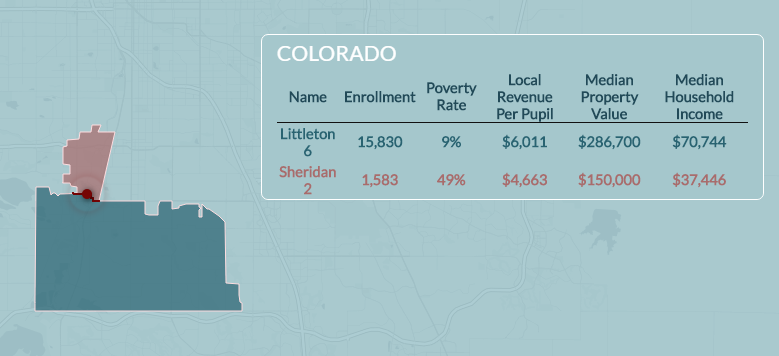

EdBuild measured gaps in poverty rates across all 33,500 school district borders in the U.S. The organization then ranked all urban and suburban borders from most to least segregating. The data revealed a local Colorado angle: the border between the Sheridan and Littleton school district’s is the ninth most segregating border in the country.

Within Littleton’s boundaries, 9 percent of residents are poor, while in Sheridan 49 percent of residents are poor. That’s a 40 percentage-point spread across the boundary. Chalkbeat recently published an excellent article on contrasts between the two districts.

Stadler stressed that EdBuild used federal poverty data, not free and reduced lunch statistics, which encompass a broader swath of the population.

“That’s a massive gap” between Sheridan and Littleton, Stadler said. Only boundaries in Michigan, Alabama, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Arizona have bigger gaps. Ohio has three boundaries with larger gaps, Alabama two.

But the biggest gap belongs to the boundary between Detroit and Grosse Point, an affluent suburb: it’s 42 percentage points, only marginally higher than Littleton-Sheridan.

That Michigan boundary was the focus of a controversial, landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1974, which many integration proponents say reversed two decades of school integration progress set in motion by the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954.

In Milliken v. Bradley, the court found that school systems were not responsible for desegregation across district lines unless it could be shown that they had each deliberately engaged in a policy of segregation. This ended mandatory inter-district integration plans, which had proven to be highly effective instruments of integration, but were loathed by many suburban residents.

EdBuild hopes to continue its research on segregating school district borders, and will share its finding with advocacy groups. The hope is that civil rights lawyers will use the Fault Lines data to file a lawsuit that might eventually overturn Milliken v. Bradley.

During the EdVenture Ed Shark Tank competition in September 2016, EdBuild won a $70,000 grant to pursue this on a deeper level. $20,000 came from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, $50,000 from the J.S. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.

EdBuild founder and CEO Rebecca Sibilia said her organization would not directly pursue litigation, but hoped to inspire others to do so. “We are just a data and numbers shop,” she said during Ed Shark Tank pitch.

That “just” strikes us a bit too modest. Check out EdBuild’s work. We’re confident you will be as impressed as we are.